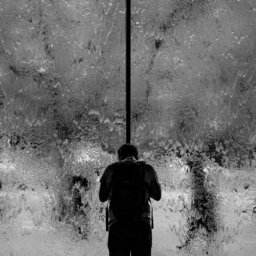

There are many things that are inspiring about India: it’s rich history and diverse culture, it’s geography that spans the Himalayan mountains of the north and the Thar desert of the West. And there are many things that are not so inspiring: the sexism, the poverty and the economic disparity.

What is perhaps most inspiring is how these two pillars of the world’s largest democracy are coming together; how its people are rising above and beyond these challenges to make India a truly unique and beautiful country. This was my experience in perhaps the very heart of a country’s beliefs and values: it’s mental health system.

I spent six weeks working in a psychiatric hospital in the Himalayan mountains in North India. These six weeks gave me an insight not only into the dark depths of the human mind, but also the fresh diversity of Indian culture, traditions, values and beliefs.

global mental health, culture

Priya* was fourteen when the first signs of mental illness began to show. It did not begin in a dramatic display of fireworks, but a poor grade in one of her end-of-school exams.

Priya’s family lived in a small village fifteen kilometres away from the main city.. The only life they knew was one of hard labour and Priya, like many impoverished families across India, was also aware of the hope that education could bring to a family such as hers.

Priya was young and determined. She spent her lunchtimes working through textbooks and her dinner times working through her homework. She woke up at 4am to memorise her facts and figures for her upcoming exams, and spent her evenings helping her mother with the housework.

It was therefore a shock when she found out she had failed a small – but vital – part of the exam. It was more than a shock. To Priya it was an earthquake to the very foundations of what made her who she was; the one person who could get her parents out of their cycle of poverty and famine, the answer to her family’s problems. This one exam was a dagger to the very heart of who she was.

It took a week before the signs of hurt began to spill over and became noticeable to the rest of the family. The first thing Priya’s mother noticed was her daughter skipping breakfast in the mornings as she rushed to school instead. Then it was the shadows under her eyes and late nights spent looking out the window.

As the days went on Priya fell down into a spiral. Her parents watched from afar as they watched their daughter – their joyful, energetic, full-of-life young daughter – crumble before their eyes. They watched as her temper became inflamed and her irritability raised tensions amongst family and friends. They watched as she lost interest in herself, as she stopped brushing her hair in the morning and screamed and cried at her parents at night. They felt lost. They went to their local temple to pray, begging to have their daughter back. But the worst was yet to come.

It was Friday evening, and darkness had set in across the Himalayan mountains as Priya’s father returned to the house, wiping his brow after working out in high temperatures all day. Her mother was just starting her work in the kitchen when the police knocked on their door: Priya had been found lying on the floor in the school bathroom having taken an overdose.

One week after this incident I met Priya in the psychiatric ward – her home for the next three weeks. During this period I got to know Priya and her family well. I began to see the closeness of this small family and the Priya’s despair reflected in her parents hearts.

What inspired me most was my conversation with her parents. Coming from a poor and uneducated background they had never heard of mental health problems before. The past few weeks had been an eye-opener for them. They had learnt to see the world through their daughter’s eyes and had begun to understand the enormous pressures that were being placed upon India’s youth. No longer was it enough to toil in the fields under a soaring sun, or to marry at a young age and relish in family life. The modern world asked for something more: perfection. The best grades by the age of twelve, the best university at eighteen and the best heart surgeon at thirty-two. The modern world was the world of competition, independence and pride. It was the clashing of West and East, family and individuality. In this whirlwind of generations clashing and suffering becoming the normal, I remembered these words from Priya’s father.

“We are learning. We are beginning to understand that India is not how it was when we were growing up. And we want our daughter to know that no matter who she grows up to be, she will always have the love and acceptance of her parents.”

global mental health, culture, depression, suicide

This is my aspiration for India’s future. It is not a hope for wealth or scientific breakthroughs. It is an appreciation of the overwhelming change that is taking place in India today, with the culture of the past meeting the technology of today. It is about the current youth of India who are trapped inside a Venn diagram, their cultural values pushing them one way and the Western world pushing them the other.

My dreams for India lie upon the hope that the mental health of India’s youth will grow with every conversation that people dare to have. My hope is that there are families like Priya’s out there who will be able to shine the light for India’s future minds and nurture them in an atmosphere that is changing everyday.

*Priya is fictional, based on my experiences in a Psychiatry Ward in Shimla. She is not based on any one person.