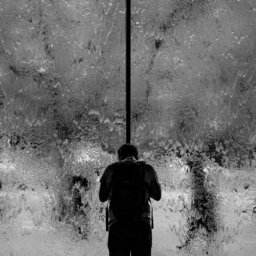

I want to reflect on what has undoubtedly been the worst job I have had since qualifying as a doctor and the impact it has had both on me as a clinician and me as a person.

I spent six months working with a community mental health team that specialised in people with, among other things, personality disorders. Personality disorders often stem from early childhood experiences and the relationships we develop with our primary caregivers. Yet there was little to no focus on the early lives of most of our patients which, if we had looked closer, would have uncovered neglect, abuse and an opportunity to appreciate the person behind the number. Instead, many (mostly young females) were given a diagnosis of personality disorder despite not meeting the diagnostic criteria but simply because they self-harmed, expressed suicidal ideation or used emergency services ‘frequently.’ There was rarely an attempt to understand the underlying reasons for this behaviour or how the person felt; rather, the focus was very much on stopping the behaviour that services deemed ‘problematic’ i.e. took up staff’s time, and once that behaviour had stopped, the person was discharged on the basis that their needs no longer met the criteria for secondary mental health care – they were still suffering, it’s just they were no longer ‘problematic.’

In the six months I was there I saw consistent blame and judgement of patients for their difficulties and futile attempts to categorise their complex lives into neat boxes. If patients were offered treatment (and they often weren’t), they were often generic approaches that did not even begin to acknowledge the uniqueness of each person’s life or the difficulties that they were going through. Instead, every person was given the generic label of ‘depressed,’ ‘anxious’ or ‘personality disordered’ without any attempt to place these difficulties within the context of the patient’s lives; every person who was depressed was deemed to be the same and personal lives were of no interest whatsoever. These generic labels led to generic treatments which inevitably failed as they simply treated a label and not a person, leading to people feeling even more hopeless and services blaming the patient for ‘not getting better,’ ‘not wanting to get better’ or ‘not engaging.’ Underlying this all was a system whose main aim was to stop people getting into mental health services – even if they needed it – and pushing people away as soon as possible, particularly those who did not fit the ‘ideal’ patient image; compliant, articulate, engaging (in the right way of course) and quick to ‘improve.’

The dominant narrative within the team was one of behaviour and responsibility; patients were often described as ‘misbehaving’ or ‘acting out’ which would lead to staff acting as stern ‘parents’ who refused to respond to their patient’s ‘childish’ responses and placed punitive measures if rules were not followed. Patients were not people and their behaviour was just that – behaviour. There was no human interaction. There was no attempt to understand why someone might self-harm or want to kill themselves; the dominant belief was that they chose to do so and that the onus was on them to stop. How? Oh, just take a bath. Or call the Samaritans. Or speak to a friend. Just don’t come to us, otherwise you’re just looking for attention.

This all resulted in a job where I was often dealing with patients who had incredibly sad and traumatic lives, with long histories of being bounced around mental health services because no one knew what to ‘do’ with them, being placed on increasing amounts of medications that took away any emotion – good or bad. My role? I still have no idea. Often I was just a receptacle for these people’s anger and frustration with services and the sense of hopelessness that they felt. I would turn to my team to ask for advice only to be told that I should discharge these people back to their GPs and that there was nothing more that could be done – or, to just increase their medication and then discharge them ‘to keep them happy.’

The more patients I saw, the more hopeless I became, just like them. I was the face of a service that did not listen or respond to their needs – it didn’t even care. It was a conveyor belt of numbers – one in, one out.

I tried at the start. I would spend hours reading through reams of medical notes, trying to understand their lives and place their sadness, spending time listening to patients and exploring their life experiences. I was told pretty early on to stop doing this; that it was pointless, that that was not the role of a doctor (what the hell was?) and that such attempts would ‘encourage’ patients to seek more of this ‘type of care.’

My role, it seemed, was to ignore people’s suffering, to assume that every person was lying to me or had an alternate agenda to try to stay with mental health services and not take responsibility for their own lives (can you imagine us trying to do this in physical healthcare?), to prescribe increasing amounts of off-licence medications to ‘make them feel like they got something from you’ and then discharge people against their wishes, ignoring any pleas for help and responding to requests for advice with ‘take a bath’ or sign-posting to other, third-party sectors who would reiterate that these individuals needed professional help and that they were limited in what they could offer as volunteers and non-professionals.

Becoming a vessel for repeated trauma and suffering, repeatedly refusing care to people who were, quite literally, begging for it, attending daily team meetings where patients were described as attention-seeking and misbehaving, working in a culture where really getting to know your patients and attempting to understand their needs was frowned upon, dealing with two patient suicides and three serious incidents in a six month period, took its toll.

There are two ways of dealing with such a situation; either you go along with the rest of the team, become desensitised to the suffering and start blaming the patient in an attempt to deal with the lack of care that you can provide, or you become overwhelmed.

For me, it was the latter. Even now, having taken a one-month break, I still dread returning to psychiatry training. I dread seeing patients now because I fear that sense of helplessness, of sitting with someone who has been so open about their struggles and then closing the door in their face. I dread giving someone a prescription that won’t work and then telling them there is nothing more I can do. I dread returning to an environment of blame and judgement. I dread working in a system that sees patients as a burden and takes away any sense of humanity. I dread working in a system that does not even try to care.

I dread it.

For a more coherent and articulate description of what I am describing, see this fantastic journal article written by Dr Beale: